Author: johnkratovil

Frogs L’Eggs

The Czech Refugee Trust Fund

There are whispered stories that in escaping from the Nazis, the Czech Government loaded a train carriage with gold and travelled to England. This gold would have been the funding for the government in exile and then, in 1945, for establishing the Czech Refugee Trust Fund. In 1945 my parents were not yet refugees. My father had been arrested when the country was invaded. Per- haps you remember this story? You would find it under ‘Munich Agreement’ in the encyclopedia of your choice. Neville Chamberlain stepping off a plane in London and waving the agreement, signed by Hitler, which was going to guar- antee Peace in our Time but which also granted the annexation of a ‘far-off country of which we know so little’. If you want to see this for yourself, type in ‘Chamberlain Munich Agreement Youtube’. How far-off was the country? How long had the flight there taken? Today it takes barely an hour. Czechoslovakia was a child of the 1918 Treaty of Versailles and the father of the new repub- lic was a philosopher named T.G.Masaryk. My father, Bohuslav G. Kratochvil was born on the 21st. of October 1901. For a thoughtful seventeen year-old the forming of an independent Republic out of two small countries that had previ- ously been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was a momentous event. Their form of government was going to be shaped by a man who was also a philoso- pher. Some see this time from the end of the First World War to the Invasion by the Nazis in 1938 as having been a period of Benevolent Paternalism. In other words, government by a father who knows best but sincerely has your best interests at heart, and these days that does sound very patronising. Here are 2 examples of the kind of legislation put in place during that period. One, that the cutlery in restaurants should be wrapped in a napkin. It is difficult to know if the fact that the knife and fork and spoon that you were about to use were any cleaner because care had been taken to wrap them in a napkin, but the intention was that they should be. The second example has more of a guar- antee. All doors to public places should be installed to open outwards to the street. This guaranteed that, if there were to be a fire at the this restaurant, or this cinema, or this art gallery, the doors to the street were going to open out and not jam you, and the others trying to escape the fire, inside the building. Bohuslav G. Kratochvil did his PhD. at Brno University, this giving him the title of Dr. This does not make you a Doctor of Medecine, but it does mean that you put a Dr. in front of your name and not a Mr.

(’Psychologie Ditete a Experimantalni Pedagogica’ Knihtiskarna Typia v Brne 1928)

From Brno University and a Doctorate in the Psychology of Children to the Ministry of Education, eventually becoming Secretary to the Minister for Education. It was as a member of the Czech parliament that my father was making his speeches about the AntiSemitism which was very much in evidence just across the border. When those borders fell, he was arrested. Now we need to find the memoir of Herbert Morawetz, and if you are looking for an account of Czechoslovakia in the interwar years, you will find this a fascinating one, but for now, this is the bit that you should read

‘Later, (Bohuslav) told me about the greatest emotional experience of his life. He was to be sentenced by a German court standing next to Ladislav, the former leader of the Czechoslovak conservative party, who had urged not to submit to the Munich dictate and who had become a prominent member of the resistance. First, the judge sentenced Ladislav to death. Then, as he sentenced Kratochvil to life in prison, Ladislav shook his hand,’Congratulations, you will live’.

(Herbert Morawetz ‘My 90 Years’. New York, 2 January 2011)

My father spent five years in various prisons in Germany. His prisoner number was ZWM 1042. He returned to Prague to take part in in the process of Reconstruction. My mother also spent time in prison. She returned to Prague and waited to be reunited with her family. Her grandparents, her Mother, Emilie Guth (nee Weigert) and father, Rudolph Guth (a lawyer, also a Dr. – a JuDr. – a Doctor of Jurisprudence), and her younger sister, Vera. She waited in vain. None of them came home. My parents had known each other before the war. My father was 16 years her senior. He was part of a group of bright young things who read P.G.Wodehouse and gave each other nicknames modelled on characters from the Jeeves stories. My father married. Her nickname was ‘La- dybird’. He never spoke of his first wife, but much years after he had died, I was told that she wrote letters to him while he was in prison, letters that would no doubt have given him heart, but during those prison years, she met someone who she fell in love with and finally told my father when he returned to Prague. Another story that came out years later was that my mother had been disap- pointed when, on one of those tennis-playing weekends in Stehovice, he had announced that he was going to be married. Helen married a young doctor whose name was Arnost Schenk. Arnost died in 1941, in the same year that the rest of her family perished. So it is 1945. The war in Europe is over. My parents meet again in Prague and marry. This will take some of the suspense out of the story, what the International Movie Database calls a ‘spoiler’, but let us go back to page 133 from the memoir of Herbert Morawetz:

‘In 1972 Boha Kratochvil, who had been a close friend of ours in Svetla, came to Belle Isle. He was by now a tragic figure. Soon after the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939, he had joined the Resistance, but was arrested and spent the rest of the war in German prisons. After the war he found out that his wife had left him and he married a much younger woman who was the sole concentration camp survivor of her family. As a hero of the resistance, he was named Ambassador to Great Britain from 1947 to 1950 and Ambassador to India from 1950 in time for that country’s Independence. By that time he had grown out of favour with the Communist government of Czechoslo- vakia and was recalled to Prague. Warned by a friend not to return, he wrote an open letter of resignation in which he spoke of communism as being at vari- ance with the spirit of the Czech people. (He sought Political asylum in Great Britain, making his flight into exile by train and by ship and using the names ’Mr. and Mrs. Smith’.) By now he was socially isolated, being blamed by his old friends for having served under the Communist regime for too long. His wife died and he made a poor living by selling stationary. When he arrived on Belle Isle, following Honza’s invitation, he was in a state of terrible excitement and

had a bad asthma attack. He told us that seeing us was for him a return to the Svetla of his youth. After a few days on Belle Isle, Boha was to stay with Honza in Toronto. He lay down in his house on a sofa, but when Honza’s daughter came to pick him up, she found that he had died.’

Let’s just jump back to 1951. The Movietone News films the arrival of the the Czech ex-Ambassador to the court of St. James who is seeking Political Asylum. He is accompanied by his wife and 3-year old son. No mention is made of his contemplating suicide during the sea voyage. Time Magazine reports interviewing a small and frightened man. The Time reporter presumably was taller and had not spent the war years in prison and was not at that time having to choose between exile from the country that he was devoted to and more years in prison. Perhaps we were not as familiar with the term ‘stress’ in 1951, but still, ‘a small and frightened man’ seems like an unfair assessment. When speaking about that choice, my father would say that, whereas he had been able to withstand the rigours of imprisonment by the Nazis (two of the years were in solitary confinement), he was not sure that he would have been able to cope with being imprisoned by his own People. Perhaps, during his research, the Time Reporter had overlooked my father’s name having been placed in the Golden Book of Jerusalem in recognition of his ‘friendship toward the Jewish people’.

Cross Words

The clue for 1 Down in the Quick crossword puzzle for Tuesday January 13, 2015, in the Sydney morning herald was: ‘List of uncompleted works’.

The 7-letter answer was ‘Backlog’.

So the name for this blog is going to be ‘Backblog’, the assumption being that many of the blogs are likely to be incomplete.

Another wild prediction is that many of the blogs are going to be inconclusive. In other words, if you are looking for answers, this is not going to be the place to find them.

Michel de Montaigne, as you all already know, was an essayist of the 16th. Century. Alain de Botton devoted a chapter of his ‘Consolations of Philosophy’ to Montaigne, and in the video version he visited the house near Bordeaux where Montaigne lived.

Some might say that Montaigne was the original Blogger. Others might say that he was the inventor of the personal essay. He made himself the subject of essays that were first published in the 1580s.

In the 1960s, a copy of Montaigne’s essays was high on my list and the two volumes of ‘Essais’ from Classiques Garnier as still in what booksellers would call VGC (very good condition). They were bought for me by a dentist who lived and worked in Nancy, which is near Stasbourg. Strasbourg lies on the border between La France and L’Allemagne. Some people also call it ‘Strasburg’.

The disarming thing about Montaigne is that, while he was someone who was endlessly looking for answers, he did not always find them and would often conclude that he did not know – ‘Je ne sais pas’.

How endearing is that in a world that looks for the black and the white in everything and does not like to admit that there might be a grey?

Quiz shows are not representative of knowledge. The core belief in a quiz show is that there is one, and only one, answer to a question.

So you want to be a millionaire?

Is London in A.France B.England C. Belgium D. Holland?

Lock in B. England?

Well sorry, London is a town in Ontario and Ontario is a Province of Canada.

So you only get 500,000. Still, well done you for knowing that Angelina Jolie was indeed in Cyborg 2 and not in Terminator 2. You had obviously done your research.

There are plenty of other Londons. There’s another on in New South Wales,

which is one of the States in Australia.

The Hound of the Kratovilles

It happened again yesterday. Seeing the name in print, an article by the daughter about which school to send her daughter to. Seeing the name, seeing the blocks of print, the Darkness rose. The article remained unread. It will never be read. This depression has always taken the wind out of my sails. I went upstairs and fixed a roller blind, I rearranged some books. I lay down and went to sleep on the floor.

The black dog of the Broinowskis. Not the Hound of the Baskervilles, the Curse of the Broinowskis. The daughter barging into my house and walking to the spiral staircase. Going up the stairs and ordering my 11 year-old son to turn his radio off. Turn his radio off because they were filming next door. He didn’t tell me until much later. He knew how upset I was going to get.

How old is he now? 34. He was 11 then. It was 23 years ago.

Usually a film production company would make arrangements about filming.

‘We will be making a commercial about fertilizer and need to film your house and the house next door. In the Ad, one of the gardens is going to be made to look lush and blooming and the one next door is going to look like crap because the people there don’t use Auntie Rhinum’s ‘Jumbo Gro’ ™. So, we would like to hire your house for the filming and dress up your garden to look lush and blooming. You don’t have to move out or anything like that. We will need 3 days, one for preparation, one for the actual filming and one for returning things here to normal. This is what we are offering to pay.’

That kind of thing.

While I was at the central School of Art and Design, I worked as a Prop van driver and later as an Assistant Prop. I stopped driving the van when I realized that I had driven through an intersection against a red light. I would get up at 4 in the morning to travel to South London to pick up the van. By the end of a day’s driving, I was so tired that all the red lights looked like the brake lights of cars up ahead.

The last job doing props was dressing up a garden with plastic flowers. It was in the dead of Winter. The ground in the garden had to be softened up with water from a kettle so that the stems of the plastic flowers could be stuck in. The frost on the slate grey rooftops was melted by two industrial fan heaters. The cast and crew were numb with cold while faking a Summer’s day. This was the glamour of the Film Business in a time when it was still using film. This was the short-sightedness of Ad Agencies, who could have commissioned the film to be made during Summer. A time before computer trickery. A time of Film Magic. A time of woollen gloves and runny noses.

Nice.

It would have been ‘nice’ if the documentary makers had said that they would be filming next door, since they would be recording sound, would it be all right if we could be conscious of that for, say, 2 hours, and try not to make any noise?

But that is not the Broinowski way. Of documentary making. Of dealing with other people who do not happen to be Broinowski people. We shall refer to them as the Broinowskis do. We shall refer to them as ‘these people’.

It is, in case it has escaped you, a perjorative term.

Refugee is not a perjorative term. Refugee means someone who is seeking refuge.

In 1960, penguin books published a report in words and Drawings by Kaye Webb and Ronald Searle with the title ‘Refugees !960’. My father bought it. It cost two shillings and sixpence. Half a Crown.

‘On the day of the inauguration of World refugee Year in Britain on 1 june 1959, the United Kingdom Committee announced a target of two million pounds. Eight months later, after herculean efforts by the committee and its constituent refugee agencies, that sum had been exceeded. Encouraged by the success of the campaign they have now doubled the national target to four million pounds, but there are still 110,000 refugees left in Europe alone, of whom 22,000 under the mandate of the United nations High commissioner for Refugees are mouldering away in camps, as most of them have been for the last fifteen years. Believing that first-hand reporting might stir pity, open pocket-books, even relax restrictions more effectively than speeches or statistics, the office of the U.N.H.C.R. invited Ronald Searle and Kaye Webb to vid sit some of the camps in Austria, Italy, and Greece. In this book they submit their report.’

And here is a newspaper clipping about the book:

‘Refugees are people.

To experience an active and constructive sympathy with refugees one must think of them as persons. That is just the impact of a brilliant booklet, ‘Refugees 1960’, a ‘report in words and drawings’, by kaye Webb and Ronald Searle, published by Penguin Books (at 2s 6d; all proceeds will go to World Refugee year). This series of sharply drawn portraits of men, women and children living in the refugee camps of Europe – the book does not extend to China or Palestine – brings one face to face with highly individual persons, not all admirable or even likeable, but all intensely alive and full of v character, real people evoking a response of sympathetic interest and concern: whereas to speak in general terms of ‘the refugees’ may prompt only the image of a faceless indistinguishable horde, moving pity without hope or help. The booklet prescribes no remedies. It simply draws the people and their lives and their troubles. How can we escape letting them down? In two ways. First, of course, to send a contribution (or another contribution) to World refugee year (at 9 Grosvenor Crescent, Lndon S.W.1) before the year ends on may 31. The other is to press for the admission of still more of the refugees to Britain – and not only the n most presentable ones. To pick only those likely to ‘make good’ and pass by on the other side of the road from the halt and the blind is to treat the refugees as things, not people.’

In 1945, the Czech government in Exile returned to Czechoslovakia. Before leaving England they established a Czech Refugee Trust Fund. This fund purchased properties in London and made them available, for rent , to Czech Refugees. It was set up to last for 30 years – until 1975.

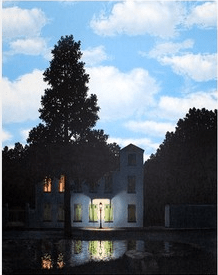

Dominion of Light by Rene Magritte

encounter of the first kind

Fee was upstairs and had been checking on the boys by looking out of the window now and then. She went to the top of the stairwell and stagewhispered down to me to get the kids in off the street. Her voice had an urgency to it, so i walked out to the deck at the front and called the boys in.

Harris Street was a quiet cul-de-sac, so it wasn’t like we were neglectful parents who let their kids play in the road. For the most part, traffic consisted of people who lived in the street, who knew where they were going and were not in a tearing hurry.

The house faced the entrance to a park and when you stood in the park and looked back at the house, what you saw was reminiscent of a painting by Magritte. It is not one of the paintings with bowler-hatted men raining from the sky. It is just a painting of a house, under a tree at twilight and the glow of one lamp which could be a streetlamp. if there is anything surreal about the painting it is in the

contrast between the lightness of the sky and the darkness of the house.

The boys weren’t annoyed about having been called home. Maybe they had had enough of being in the park. They might have gone upstairs. They still had the little garden at the back to play in. Everything was little. It was a little wooden house in an area of little houses, little gardens and little streets.

‘Did you see him?’

– Who?

‘That man who’s sitting on the road divider’

– You mean the guy in a mac?

‘Yes. Did you get a good look at him?’

-Not really. Is he why you got me to get the boys in?

‘Well, if you had bothered to take look, he was pretty strange and he was talking on one of those mobile phones. that’s just the sort of thing that they use to hook little boys. like that guy at the school who was asking kids if they would help him look for his puppy. If Wendy hadn’t seen him in time and known that he wasn’t Carlos’s dad, we’d all be reading about another missing child in the news.’

– Stranger Danger?

‘Go back out and take another look’

He was still sitting on the low divider. The coat he was wearing was unusual, unusual because people in Sydney do not dress smartly. The weather is too changeable to know what to wear. If it is consistently cold, like it can be in Melbourne, then you can afford to make a fashion statement. In Sydney, you can wear a suit if you go to work in an air-conditioned car and park it in the basement of the car park of the air-conditioned building where you have an air-conditioned office, but most people wear shorts and t-shirts, clothes that you can throw off and go for a swim when you overheat. The other unusual thing was that he was talking into a mobile phone. More than 20 years ago, a mobile phone was something of a novelty. It was the sort of thing that could get the attention of adults, let alone small boys.

There was something not quite right about him. He was looking at the house next door. My guess was that he was talking someone on the phone about the house. Perhaps he was going to buy it, or had already bought it.

Our neighbour had been Joelle who lived with her son, Job. Job like in the Bible. Pronounced with a big round ‘O’. like JOhb in the Bible. Job borrowed my air pistol and never gave it back. Joelle’s brother had helped her do things to the house. When they had called out for help, we had run in and helped support a beam that he was putting in. If the beam had collapsed, the whole house would have collapsed too. He brother borrowed my books about the Craftsman Builder and the Woodbutcher’s Art and never gave them back.

She put the house up for sale, but it turned out that the new owners were not going to live there.

So while the house was being rented, we were going to be granted a little longer to live there.

Jal-Azad

Spigot

Part number 06-230-7

There is a moulded piece of plastic at the back of the clothes dryer which is called a spigot.

It has an intricate parts number because it is an intricate moulding.

It is the spindle that you press the mesh onto so that the mesh can catch the lint. You know. That net the size of a dinner plate that you take off before each drying session and then pull apart to get at all the lint that was produced by the last load of washing.

Pulling the lint off can be a satisfying experience if you manage to catch a corner of it on the first go and then peel all the rest off.

Sometimes it is as easy as peeling a mandarin. At other times it is as hard as peeling a stubborn orange. One of those grumpy Spanish oranges that does not wish to be peeled.

A sixty-third generation Spanish Inquisition orange that wants to keep its skin on.

Paula comes and tells me that there is a problem with the dryer. A bit of plastic has broken off the bit at the back and now the lint filter won’t stay in place and the machine won’t work.

What actually happens is that Paula comes and says ‘Jawn’. She then says ‘Jawn’ because she wants to be sure that she has got my complete attention.

‘Jawn. Can jew come here for one minute’. No question mark. This is not a question. What Paula means is ‘Come here. Come here now. Come and look at this. I have sometheen to show jew’. And please make note of the ‘one minute’. Note that she is not saying ‘a minute’. Paula is being quite specific that the number of minutes will only be One.

One Paula Minute is one of the many reasons why I have not written a novel. Or a short story. Or an email.

Or a note to myself which would remind me that I really need to have a word with Paula about my need to concentrate.

Together we walk to the dryer. When we get there she says, ‘One second’.

She says ‘one second’ because she has just noticed that the washing machine has completed its cycle and has decided that it is really important to empty the washing machine before she is going to take the one minute to espline me what it is that she wishes to espline.

After the one second has elapsed, the meter starts running on the one minute.

And at the end of the one minute, Paula has esplined me that there is a problem with the dryer. A bit of plastic has broken off the bit at the back and now the lint filter won’t stay in place and the machine won’t work.

The bit at the back is the bit that should be called a spindle but which the manufacturer calls a spigot.

I always thought that a spigot was something to do with beer. Something like a tap that you would whack into the side of a tankard and use to control the flow of the mead or homebrew or ale. Or even rum.

Or is that rhum?

Ok so long as it isn’t rheum or rhume.

You wouldn’t catch me turning the spigot on a tankard with ‘rheum’ stenciled on the side.

But Westinghouse call it a spigot, so let’s call it a Spigot because at least that is a bit more romantic than calling it Part Number 06-230-7.

What do you do when your spigot is broken? Certainly suicide is an option that flits past in the background.

What is the name of that place on Oxford Street in Paddington? Is it Oxford Electrical? Oxford Supplies? Oxford Electrical Supplies?

Let’s try the Yellow Pages Online because we are so hip and groovy and so switched on.

Let’s Google.

Google ‘yellow pages’.

Google gets us the address for Yellow Pages. Click on the address. Up come the yellow pages. And here come a lot of other windows that are opening themselves up although they have not been invited to do so. ‘Try Me!’, ‘Buy Me!’, ‘Me, Me, Me!’, ‘Oh Please, Sir, Me!’ But you have to be cruel and shut them all down. And shutting them all down is like spending a bit of time out at a carnival sideshow shooting lead pellets at sheet metal ducks in the hope of winning a fluoro green teddy bear.

Before the Yellow Pages are about to let you know anything they want to know who you are and where you live, your mother’s maiden name and the name of your pet.

‘Is this really necessary?’

– Yes. Sorry. Fair’s fair. You want something from us, we want something from you.

‘Well, I want the name of an electrical wholesaler.’

– Oh do you now?

Or Treat

OR TREAT

‘Dad, Dad, Dad. Quick. I need some shaving foam’

– Shaving foam? What for?

‘Oh come on, quick Dad. Its Halloween’

– Halloween? Since when do we do Halloween?

‘Come on, Dad. hurry up’

– What’s the magic word?

‘Please please please please please oh please’

This last ‘Please’ drawn out into the long squeal of someone who needs to go to the bathroom

Urgently

And sounding more like

‘Pleeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeezzz’

– Actually, it is Abracadabra.

‘Dad’.

When Zac says ‘Dad’ like that, you have to get serious.

– It’s in the bathroom cabinet, along with…….

‘Thanks, Dad’

– Hey. Hold on a Sec. What’s shaving foam for?

‘No more Secs, Dad. Gotta go. David Vered’s Dad’s coming’

And he’s gone.

Did he just say ‘no more sex’?

I try to go back to reading, but find myself trying to form a mental picture of David Vered and then, when that fails, trying to remember if I know what his Dad looks like.

That’s it. I can’t read.

I put the book down on the sofa next to me and then I put my reading glasses on top of the book. Halloween? Since when do we do Halloween in Australia? And what is Halloween anyway? Isn’t it when kids dress up in spooky costumes and go out at night looking to get the bags that they carry filled with chocolates and sweets and marshmallows and toys? Isn’t it when evil people put razor blades into apples and muffins to scar the mouths and tongues of the kids who come round looking for treats?

How could Anne-Marie have agreed to this?

I get off the sofa and head out into the garden.

Anne-Marie is kneeling on a green rubber mat and there is dirt scattered over the paving stones. A tray of seedlings from the Arcadia Nursery wait patiently to be given their new homes in the flowerbed.

– Which one is David Vered?

Anne-Marie is used to being asked silly questions out of a clear blue sky. She wipes the back of a gloved hand over her forehead, and the brim of her straw hat tilts back to a cute angle.

‘He’s the wild one. You know, the one who got suspended for the rest of the term’

– Uh huh.

Seeing that nothing has really registered, she goes on

‘The little dark-haired one. The one you said has eyes like little black ball bearings’

– Oh him. What’s his dad like?

‘His dad? His dad is wilder than David. He has that greasy pompadour hairdo and always wears Hawaiian Shirts’

– I don’t think I’ve met him

‘Oh you would remember if you had’

– And you think its ok for Zac to be going off with them?

‘What? When?’

– Well, today. Now. For Halloween.

She pales and I realize that I have screwed up. Again.

Running through the house is a blur. The cats scatter. I manage not to crash into any furniture and make it out to the street without breaking anything.

Zac is still standing in front of the house

– Did you tell Mum that you were going out?

‘Course’, he says, looking up and down the street and shaking the can of foam.

– Well Mum doesn’t seem to know about it

It isn’t that Zac ignores what I am saying, he doesn’t hear what I have said

Noone could have heard

The roar is like the rattling blast of a gang of unmuffled Harleys and the monster car appears at the end of the road

It is a deep metallic purple and it is huge

It has a mouth at the front that looks like something carved into a pumpkin, but with teeth that have been chromed. It has fins that rise up at the back like the wake behind two jetskis.

It is so wide that it fills the street, almost touching the parked cars on either side. Like Halloween, this Land Barge would be at home in America.

The car has no roof. Maybe it is a convertible, maybe it simply never had a roof. Sloshing about like shrimps in a bucket there must be ten or twelve kids already in there.

The man at the wheel is wearing sunglasses that are so black that they censor his face like the black bar in a newsphoto. Slick hair, Hawaiian shirt, just like Anne-Marie said. The noise is ear-splitting. The man is waving Zac in and Zac vaults over the side.

He may not have meant for me to get in, but I clamber in too. The car is rolling. It hadn’t really stopped. I look back to the house and Anne-Marie is a picture framed in the doorway. She is a photo of a newlywed bride whose husband left for war on the day of the Wedding. She looks brave but forlorn. And so does the little seedling she is holding, except he doesn’t look half as brave. The photo and its frame get smaller as we rumble down the street.

When the picture is out of sight I turn to see where we are going but the windscreen is covered in spidery yellow strands of plastic. The driver is looking over the rim and steering with one hand on something that looks like a doorknob attached to the steering wheel. With the other he is setting fire to a cigarette with a device that he has pulled from a hole in the dashboard.

Mercifully the noise makes conversation impossible, because all I can think of to say is ‘Who the hell are you and what the fuck do you think you are doing?’.

I feel the icky goo being jetted onto the back of my head and when I turn to see which of the little angels I can thank for that, it jets into my eyes.

The yellow goo stings and the reflex makes me jerk my head back onto something sharp. Now I don’t know whether to hold the back of my head or wipe the stuff out of my eyes. I feel something that I haven’t felt for years. The warm trickle of blood seeping into my hair and the way it turns cold in the air.

I am blinded, in pain and my son and I have been kidnapped by a man with a car called Mogul or Nabob or ThunderChief who is either crazy or pushing his envelope on being an Extrovert.

The car stops rolling and the sound of the motor idling is only marginally quieter than the sound of it running. I can get my eyes open but there is still yellow sticky stuff in my eyelashes that interferes with what I can see. I can see that the boys have piled out of the car and are at the front door of a house. I look for the driver but he is not there. I shift over to the driver side to look for the ignition key and shut the damn thing down, but there is no ignition key. There is no ignition. There are lots of dials and knobs and buttons and levers, but nothing that says ‘On or ‘Off’.

The brick going through the window is what makes me look up at the house. The front garden has been torn up. One of the kids is hefting a garden gnome to take out another pane of glass. Zac is emptying my can of shaving foam into the letterbox in the door.

Little David, his black BB eyes shining, is waving the others back to the car. They cascade back towards me like bats flying out of a cave, but they run to the back of the car. I can’t see them because the lid of the trunk is up.

When I get back there the driver is handing out all kinds of stuff. There are hats and wigs and capes and pumpkins. There are greasy jars of makeup. There are crates of beer, bottles of vodka, a jerrycan which might have petrol in it. There’s an open box of what look like fireworks, some greasy rags, an M16 automatic rifle and, rolling around loose, some things that are either grenades with hair stuck to them or blackened shrunken heads with their mouths sewn shut.

When the driver slams the lid closed, there is only a moment to take in the monstrous brake lights that are mounted on the monstrous fins. They are like rearward facing missiles. They are a cross between an enormous red lipstick and a sign that says ‘Fuck you’ more than it says ‘Slow down because I am slowing down’.

But there is no slowing down. I have to run alongside and haul myself in over the door in a way that makes all the kids laugh. The car careens around a narrow corner into a street that was never intended for cars like this. The left front fender lops small peppercorn trees off at the knees. The driver touches the brakes and, as the car slows, the kids tumble out like paratroopers. This might be the moment to try and grab Zac and take him back home. I look at the driver to see if it might be possible to reason with him.

The dull crump of an explosion blows the glass out of every window in the house. The kids all pile back into the car and the tyres squeal and make smoke. The car scrapes along all the cars parked on that side of the road. Kids are lobbing stuff out of the car as another house goes up in flames.

It isn’t even dark yet. Those flames won’t be lighting up the night sky. Dusk still has to come before night falls and that isn’t likely to happen for a while.

I try to grab at the driver’s arm to and let him know that I want him to stop, but his sunglasses stare back at me and he smiles and offers me a cigarette.

I haven’t smoked in twelve years, but this one tastes great. You would have thought that I’d be coughing and spluttering all over the place but, dammit, it’s just like I had my last cigarette five minutes ago.

When I see that the kids are filling bottles with petrol and stuffing rags into the tops, I get rid of the cigarette faster than if Zac had caught me smoking. What the hell am I doing? There he is, his face blacked out in tiger stripes like a Commando, making Molotov cocktails with the rest of them. One of the little tykes is bundling sticks of dynamite with electrical tape.

Halloween Night is still young.

The growl of the car goes deeper as we climb uphill. The driver is still weaving slightly from side to side, but the parked cars keep us on track as we caroom from side to side. He climbs up and sits on the back of the seat. He steers with his foot. I signal to the kids to keep their arms and legs inside the car.

How safety conscious of me.

What a good Dad I am.

From up here at the top of the hill, we can see the whole of Eastern Sydney below us. On the other side is the mighty and majestic Pacific Ocean.

Pacific.

How did it ever get a name like that?

Over there are the palls of smoke rising from the second street that we hit.

Over there is the dull orange glow of the sun setting.

The driver lights up another cigarette with his last one. He flips the last one away and slides down into his seat and then a miracle, he shuts down the engine. I don’t see how he does it, but the noise stops.

We can talk.

Maybe after the ringing stops in our ears I can be heard.

He speaks. The driver speaks. I can see his mouth moving.

I say ‘What?’ and make body language that says ‘I can’t hear you’.

He makes body language that says ‘Nice here, innit?’

And then, with smoke curling out of his mouth, he says ‘Nice here, innit?’

And I can hear what he is saying.